Growth is INCREASING AT A DECREASING RATE for: Inventory Levels, Inventory Costs, Warehousing Utilization Warehousing Prices, Transportation Utilization, and Transportation Prices. Warehousing Capacity and Transportation Capacity are CONTRACTING.

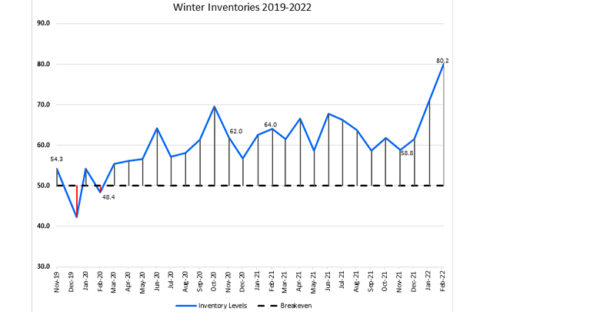

February’s overall LMI reading of 75.2 is the second-highest in the history of the index, up (+3.3) from January’s reading of 71.9. This is now 13 consecutive months over 70.0, which we would we would classify as significant expansion, with no obvious signs of a slowdown on the horizon. Like January, this month’s growth is driven by rapid growth in Inventory Levels, which are up 9.1 points to 80.2 – crossing the 80.0 threshold for the first time and shattering the previous record of 72.6. This is a complete 180 from the Fall of 2021, when firms struggled to build up inventories. Now it seems that a combination of over-ordering to avoid shortages, late-arriving goods due to supply chain congestion, and a softening of consumer spending has created a logjam, Inventory Levels a full 21.4 points higher than they were in November. Unsurprisingly, this has spilled over to Inventory Costs as well, which have also reached a new peak (+2.3) of 90.3. This inventory issue seems more pronounced for downstream retailers, who reported significantly higher levels of both Warehousing and Transportation Utilization than their upstream counterparts.

February’s overall LMI reading of 75.2 is the second-highest in the history of the index, up (+3.3) from January’s reading of 71.9. This is now 13 consecutive months over 70.0, which we would we would classify as significant expansion, with no obvious signs of a slowdown on the horizon. Like January, this month’s growth is driven by rapid growth in Inventory Levels, which are up 9.1 points to 80.2 – crossing the 80.0 threshold for the first time and shattering the previous record of 72.6. This is a complete 180 from the Fall of 2021, when firms struggled to build up inventories. Now it seems that a combination of over-ordering to avoid shortages, late-arriving goods due to supply chain congestion, and a softening of consumer spending has created a logjam, Inventory Levels a full 21.4 points higher than they were in November. Unsurprisingly, this has spilled over to Inventory Costs as well, which have also reached a new peak (+2.3) of 90.3. This inventory issue seems more pronounced for downstream retailers, who reported significantly higher levels of both Warehousing and Transportation Utilization than their upstream counterparts.

There is a possibility that this surge in inventories will result in some price markdowns for durable goods. However, it seems unlikely that this will lead to a meaningful break in the inflation we have observed across supply chains, as Warehousing and Transportation Prices remain high due to the continued mismatch in demand and available capacity.

There is a possibility that this surge in inventories will result in some price markdowns for durable goods. However, it seems unlikely that this will lead to a meaningful break in the inflation we have observed across supply chains, as Warehousing and Transportation Prices remain high due to the continued mismatch in demand and available capacity.

Researchers at Arizona State University, Colorado State University, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rutgers University, and the University of Nevada, Reno, and in conjunction with the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) issued this report today.

Researchers at Arizona State University, Colorado State University, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rutgers University, and the University of Nevada, Reno, and in conjunction with the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) issued this report today.

Results Overview

The LMI score is a combination of eight unique components that make up the logistics industry, including: inventory levels and costs, warehousing capacity, utilization, and prices, and transportation capacity, utilization, and prices. The LMI is calculated using a diffusion index, in which any reading above 50 percent indicates that logistics is expanding; a reading below 50 percent is indicative of a shrinking logistics industry. The latest results of the LMI summarize the responses of supply chain professionals collected in February 2022. Overall, the LMI is up (+3.3) from January’s reading of 71.9. The growth in this month’s index is fueled by metrics from across the index. Unseasonably high rates of inventory accumulation stand out among these metrics, but capacity remains constrained, and prices continue to grow quickly. Looking forward, respondents do not predict much relied over the next 12 months. Given the current shortages in capacity, it is difficult to disagree with them.

The LMI score is a combination of eight unique components that make up the logistics industry, including: inventory levels and costs, warehousing capacity, utilization, and prices, and transportation capacity, utilization, and prices. The LMI is calculated using a diffusion index, in which any reading above 50 percent indicates that logistics is expanding; a reading below 50 percent is indicative of a shrinking logistics industry. The latest results of the LMI summarize the responses of supply chain professionals collected in February 2022. Overall, the LMI is up (+3.3) from January’s reading of 71.9. The growth in this month’s index is fueled by metrics from across the index. Unseasonably high rates of inventory accumulation stand out among these metrics, but capacity remains constrained, and prices continue to grow quickly. Looking forward, respondents do not predict much relied over the next 12 months. Given the current shortages in capacity, it is difficult to disagree with them.

The obvious place to start this month is with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Beyond the truly tragic loss in human life, a number of costs are extending out of this conflict – many of which will have a direct effect on global supply chains. The most apparent change has been the shock to fuel prices. The price of crude oil is up to $100 a barrel – the highest level since 2014.  As sanctions rack up on Russia, prices may continue to increase, potentially driving transportation and inventory costs higher[1].

As sanctions rack up on Russia, prices may continue to increase, potentially driving transportation and inventory costs higher[1].  Average diesel prices in the U.S. $4.006 on February 28th. This is up 44 cents per gallon since the start of 2022 and up $1.07 from this time last year[2] [3]. Russia’s invasion has also led to no-fly zones over Moldova, Eastern Russia, and Ukraine, cutting off the most direct route between Europe and Asian. Additionally, many countries, such as the UK have banned Russian carriers from landing there[4]. FedEx and UPS have also suspended shipments to Russia, with packages in route to be returned to sender[5]. The longer routes cargo planes will have to take, along with increased fuel costs due to the war, create a “double whammy” for carriers. Finally, we are likely to observe various indirect costs here as well, as sanctions cut off access to leading producers of commodities like nickel, palladium, natural gas, wheat, grain, and sunflower oil. The ripple effects from this will be felt in products from groceries to Volkswagens[6].

Average diesel prices in the U.S. $4.006 on February 28th. This is up 44 cents per gallon since the start of 2022 and up $1.07 from this time last year[2] [3]. Russia’s invasion has also led to no-fly zones over Moldova, Eastern Russia, and Ukraine, cutting off the most direct route between Europe and Asian. Additionally, many countries, such as the UK have banned Russian carriers from landing there[4]. FedEx and UPS have also suspended shipments to Russia, with packages in route to be returned to sender[5]. The longer routes cargo planes will have to take, along with increased fuel costs due to the war, create a “double whammy” for carriers. Finally, we are likely to observe various indirect costs here as well, as sanctions cut off access to leading producers of commodities like nickel, palladium, natural gas, wheat, grain, and sunflower oil. The ripple effects from this will be felt in products from groceries to Volkswagens[6].

On the other side of the globe, the number of ships waiting off the coast of LA/Long Beach was at 66 during the last week of February – the lowest level since September. Additionally, dwell time for containers at the Port of LA are down 23% from their peaks in early December. However, the number of ships queuing off of alternate US ports like Charleston or New York/New Jersey has increased steadily[7]. Over 30 ships lingered off the Port of Charleston in late February – up from 19 in January. The Port Authority expects the backlog to clear by April[8]. In addition to the ongoing port delays, protests at the U.S./Canada border have slowed truck traffic as well. These actions caused prices to ship goods from Canada to the US to jump up 44% from January to February[9]. The push to avoid bottle necks has also led some firms to move what would usually be intermodal freight by road. US intermodal transports are down by 12% year-over-year through the first six weeks of 2022. They have lost approximately 1% of their market share to long-distance trucking since the start of the pandemic. Increasing the demand for truckloads of over 500 miles[10].

The impacts of this consistent congestion, fueled by the 10.6 million TEUs that were processed at the Port of LA in 2021 – up 16% from 2020[11], a paltry 42.2% of container ships arrived on time in 2021 – down 35.8% from 2019. This has not improved much, in late February the average container was still taking 109 days to get from China to its final point of destination in the U.S., something that should take 40-60 days pre-pandemic. This has led to the forecasting headaches and a high volume of late-arriving products, partially explaining why Inventory Levels are up (+9.1) so significantly to an all-time high of 80.2. Unsurprisingly, the combination of too much inventory and expensive shipping has driven up Inventory Costs as well (+2.3) to an all-time high reading of 90.3. Due to the high costs and slower sales, many firms are using their excess inventory as collateral to pay back the money they spent for expensive shipping on the way into the U.S.[12]. For both of the inventory metrics to be at an all-time high is especially unusual given that it’s February, which is often a slower time in supply chains with the wind down form Q4 and the Chinese New Year.

The high volume of inventory in the system has led to increased Warehousing Utilization (+3.3), up to 74.3 overall in February (driven particularly by downstream utilization rates of 81.1). The high levels of inventory coursing through supply chains highlights the continued contraction in available warehousing.

The high volume of inventory in the system has led to increased Warehousing Utilization (+3.3), up to 74.3 overall in February (driven particularly by downstream utilization rates of 81.1). The high levels of inventory coursing through supply chains highlights the continued contraction in available warehousing.  Warehousing Capacity is once again down (-4.6) to 43.4, the lowest level since the start of the Q4 inventory buildup in August 2021. This also marks 18 consecutive months of contraction, incentivizing many firms to aggressively explore alternative. Walmart is one such firm, as they are attempting to supplement their network by attaching approximately 100 new automated fulfillment centers to existing stores[13]. This type of large capital expenditure is obviously not an option for everyone, many smaller warehouse operators are attempting to cut costs through automation – not just with expensive robotic automation, but with digital/touchscreen picking systems that allow them to go paperless as well[14]. The impact of all of this can be seen on Warehousing Prices, which are up slightly (+0.5) to 86.4.

Warehousing Capacity is once again down (-4.6) to 43.4, the lowest level since the start of the Q4 inventory buildup in August 2021. This also marks 18 consecutive months of contraction, incentivizing many firms to aggressively explore alternative. Walmart is one such firm, as they are attempting to supplement their network by attaching approximately 100 new automated fulfillment centers to existing stores[13]. This type of large capital expenditure is obviously not an option for everyone, many smaller warehouse operators are attempting to cut costs through automation – not just with expensive robotic automation, but with digital/touchscreen picking systems that allow them to go paperless as well[14]. The impact of all of this can be seen on Warehousing Prices, which are up slightly (+0.5) to 86.4.

While truck mileage was up overall in 2021 (at an all-time high of nearly 300 billion miles[15]), U.S. Bank, in its fourth-quarter 2021 National Shipments Index, reported a decline in freight shipments of 2.4% from the third quarter of 2021 and a year-over-year drop of 5.1% from the fourth quarter of 2020. Yet for the same period, the bank’s National Spend Index, which measures freight expenditures, increased 8.4% from the third quarter and surged 20.2% from the fourth quarter a year ago. Schneider’s recent fourth-quarter 2021 results clearly illustrate this dynamic: The company’s average weekly revenue per truck was $4,521, up 18% from last year, while the average number of trucks operating declined 5.3%[16]. So, less trucks are available, and those that are around are quite expensive. This is reflected in the continued contraction in available Transportation Capacity which read in at 44.4. While the month-over month drop (-0.3 from January) is rather mild, the longevity of the contraction, now stretching 20 months back to June of 2020 is anything but. To deal with this capacity issue, many large trucking companies are planning to use their increased operating revenue to make significant capital investments. JB Hunt planned to increase net capital expenditures by over $600 billion from 2021, with Old Dominion planning to increase by around $400 million. The backlog of components continues to be an issue. North American truck manufacturers produced 264,500 class 8 trucks in 2021 – nearly 65,000 less than the 330,000 they could have produced if not shortages existed. They will be similarly short this year, projected to produce only 300,000 of the previously predicted 360,000 in 2022[17]. Even ocean carriers are moving to get in on the opportunity, with Maersk is attempting to use their record profits to break into the trucking and domestic 3PL business. The arrow is clearly pointing up in terms of the demand for these businesses with shippers spending 8-9 times more on domestic logistics than on ocean freight. This may mark a trend towards logistics companies putting together full-service end-to-end networks[18]. Even with this investment, the transportation crunch cannot be solved until the semiconductor shortage ends – something experts say could begin to ease by 2023 at the earliest[19] (DC Velocity Staff, 2022).. In the meantime, Transportation Utilization continues to increase (+6.1) to 68.5. As with Warehousing Utilization, this is driven by the high levels of downstream utilization – which read in at 75.0. A shortage of equipment is not the only thing driving transportation issues, there is the shortage of drivers as well. Part of the labor issue can be attributed to an estimated 25% of driving schools not reopening after the pandemic Frantz, 2022). As they have for the last 21 months since May of 2020, Transportation Prices expanded (+0.3) at a rate of 89.0. FreightWave’s Zach Strickland[20] notes that contract rates for dry van truckloads are up approximately 25% over the last year. The cost of freight transportation overall is up 28% since the start of 2019 – the producer price index is up 23% over that same period. Essentially, the price increases for transportation stand out even above all of the other inflation happening throughout the economy[21] (Strickland, 2022)

While truck mileage was up overall in 2021 (at an all-time high of nearly 300 billion miles[15]), U.S. Bank, in its fourth-quarter 2021 National Shipments Index, reported a decline in freight shipments of 2.4% from the third quarter of 2021 and a year-over-year drop of 5.1% from the fourth quarter of 2020. Yet for the same period, the bank’s National Spend Index, which measures freight expenditures, increased 8.4% from the third quarter and surged 20.2% from the fourth quarter a year ago. Schneider’s recent fourth-quarter 2021 results clearly illustrate this dynamic: The company’s average weekly revenue per truck was $4,521, up 18% from last year, while the average number of trucks operating declined 5.3%[16]. So, less trucks are available, and those that are around are quite expensive. This is reflected in the continued contraction in available Transportation Capacity which read in at 44.4. While the month-over month drop (-0.3 from January) is rather mild, the longevity of the contraction, now stretching 20 months back to June of 2020 is anything but. To deal with this capacity issue, many large trucking companies are planning to use their increased operating revenue to make significant capital investments. JB Hunt planned to increase net capital expenditures by over $600 billion from 2021, with Old Dominion planning to increase by around $400 million. The backlog of components continues to be an issue. North American truck manufacturers produced 264,500 class 8 trucks in 2021 – nearly 65,000 less than the 330,000 they could have produced if not shortages existed. They will be similarly short this year, projected to produce only 300,000 of the previously predicted 360,000 in 2022[17]. Even ocean carriers are moving to get in on the opportunity, with Maersk is attempting to use their record profits to break into the trucking and domestic 3PL business. The arrow is clearly pointing up in terms of the demand for these businesses with shippers spending 8-9 times more on domestic logistics than on ocean freight. This may mark a trend towards logistics companies putting together full-service end-to-end networks[18]. Even with this investment, the transportation crunch cannot be solved until the semiconductor shortage ends – something experts say could begin to ease by 2023 at the earliest[19] (DC Velocity Staff, 2022).. In the meantime, Transportation Utilization continues to increase (+6.1) to 68.5. As with Warehousing Utilization, this is driven by the high levels of downstream utilization – which read in at 75.0. A shortage of equipment is not the only thing driving transportation issues, there is the shortage of drivers as well. Part of the labor issue can be attributed to an estimated 25% of driving schools not reopening after the pandemic Frantz, 2022). As they have for the last 21 months since May of 2020, Transportation Prices expanded (+0.3) at a rate of 89.0. FreightWave’s Zach Strickland[20] notes that contract rates for dry van truckloads are up approximately 25% over the last year. The cost of freight transportation overall is up 28% since the start of 2019 – the producer price index is up 23% over that same period. Essentially, the price increases for transportation stand out even above all of the other inflation happening throughout the economy[21] (Strickland, 2022)

Movements in Inventory Levels from November 2019 to February 2022 are presented below. The readings from the last three November’s (usually near the height of Q4 inventory buildups) and February’s (when Inventory Levels are often down) are highlighted here for the purpose of demonstrating how unusual the last three months have been. From November 2019 – February 2020 Inventory Levels were down 5.3 points, from November 2020 – February 2021 they were up 2.0 points, from November 2021 – February 2022 they are up 21.4 points. This type of movement would be notable in any 4-month period, but it particularly notable now, in a time when inventories are not generally high (the all-time LMI average for February Inventory Levels is 62.8). Firms will now have to decide what to do with this unseasonably high inventory. Will they be sold at a discount? Or stored in increasingly expensive warehouses and backrooms? Neither option is ideal, and it will be fascinating to observe the different strategies that are deployed over the coming months.

From November 2019 – February 2020 Inventory Levels were down 5.3 points, from November 2020 – February 2021 they were up 2.0 points, from November 2021 – February 2022 they are up 21.4 points. This type of movement would be notable in any 4-month period, but it particularly notable now, in a time when inventories are not generally high (the all-time LMI average for February Inventory Levels is 62.8). Firms will now have to decide what to do with this unseasonably high inventory. Will they be sold at a discount? Or stored in increasingly expensive warehouses and backrooms? Neither option is ideal, and it will be fascinating to observe the different strategies that are deployed over the coming months.

The index scores for each of the eight components of the Logistics Managers’ Index, as well as the overall index score, are presented in the table below. Six of the eight metrics show signs of growth – at increasing rates from January, while both capacity metrics continue their runs of contraction. The logistics industry remains tight, and based on future predictions and industry experts, seems likely to stay that way throughout 2022.

| LOGISTICS AT A GLANCE | |||||

| Index | February 2022 Index | January 2022 Index | Month-Over-Month Change | Projected Direction | Rate of Change |

| LMI® | 75.2 | 71.9 | +3.3 | Growing | Increasing |

| Inventory Levels | 80.2 | 71.1 | +9.1 | Growing | Increasing |

| Inventory Costs | 90.3 | 87.9 | +2.3 | Growing | Increasing |

| Warehousing Capacity | 42.4 | 47.1 | -4.6 | Contracting | Decreasing |

| Warehousing Utilization | 74.3 | 71.0 | +3.3 | Growing | Increasing |

| Warehousing Prices | 86.4 | 85.9 | +0.5 | Growing | Increasing |

| Transportation Capacity | 44.4 | 44.8 | -0.3 | Contracting | Increasing |

| Transportation Utilization | 68.5 | 62.4 | +6.1 | Growing | Decreasing |

| Transportation Prices | 89.0 | 88.7 | +0.3 | Growing | Increasing |

This month, both upstream (blue bars) and downstream (orange bars) firms reported considerable rates of continued growth in utilization of logistics services. Downstream firms in particularly reported higher rates of both Warehousing and Transportation Utilization.

The inventory deluge discussed above has clearly made its way downstream, to the retailers who placed large orders to avoid the predicted Q4 shortages. Downstream firms reported significantly higher rates of both Warehousing Utilization (+11.4) and Transportation Utilization (+10.2) relative to the upstream counterparts. The ongoing lack of capacity combined with the unseasonable high levels of inventory have incentivized downstream firms to utilize every square inch of capacity as supply chains continue to labor under increased volume.

| Inv. Lev. | Inv. Costs | WH Cap. | WH Util. | WH Price | Trans Cap | Trans Util. | Trans Price | LMI | |

| Upstream | 82.8 | 90.3 | 45.5 | 69.7 | 84.6 | 50.0 | 64.8 | 88.6 | 71.3 |

| Downstream | 78.4 | 89.8 | 38.9 | 81.1 | 89.5 | 44.6 | 75.0 | 90.2 | 73.0 |

| Delta | 4.4 | 0.5 | 6.6 | 11.4 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 10.2 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Significant? | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Marginal |

Respondents were asked to predict movement in the overall LMI and individual metrics 12 months from now. Their predictions for future ratings are presented below. For the next year, respondents predict a growth rate of 69.9, down slightly (-0.8) from January’s future prediction of. This would portend significant levels of growth throughout 2022 – comfortably above the all-time average of 65.0. This growth is projected to be driven by continued cost growth, with all three metrics reading somewhere in the 80’s. Some Transportation Capacity is expected to come online (reading in at 59.0), but Warehousing Capacity is predicted to remain stagnant, barely moving at a rate of 51.8. This pessimism is likely related to the prediction of Inventory Levels expanding at a rate of 74.3. This suggests that respondents do not anticipate enough additional capacity coming online over the next 12 months to sufficiently makeup the current supply demand mismatch.

The exact nature of the future predictions varies by supply chain position. This month we see that most clearly in the predictions for future Transportation Capacity and Warehousing Prices.

In February 2022 we detected marginal or significant differences between Upstream and Downstream predictions for three of the eight components of the LMI. Similar to the current day comparisons, Downstream firms anticipate maintaining a greater rate of both Warehousing (+18.1) and Transportation Utilization (+9.2). Downstream firms also anticipate continued contraction in Warehousing Capacity at 46.7 – down from Upstream predictions of stead growth at 56.1. This could be a function of the more expensive, harder-to-find types of urban warehousing that downstream retailers are currently trending towards.

| Futures | Inv. Lev. | Inv. Costs | WH Cap. | WH Util. | WH Price | Trans Cap. | Trans Util. | Trans Price | LMI |

| Upstream | 76.6 | 84.1 | 56.1 | 69.7 | 84.4 | 61.6 | 66.9 | 83.6 | 70.0 |

| Downstream | 72.2 | 83.0 | 46.7 | 87.8 | 82.6 | February 2022 Logistics Manager’s Index Report® |